An Everyday DNA blog article

Written by: Sarah Sharman, PhD, Science writer

Illustrated by: Cathleen Shaw

It is Monday morning, and Carolyn has a big presentation at work. Despite getting a good night’s sleep, she wakes up exhausted, and her joints are stiff and painful. ‘The invisible monster strikes again!’ Carolyn thinks to herself. ‘Of all the days to have a flare-up it just had to be today.’

The invisible monster Carolyn is referring to is lupus, an unpredictable and misunderstood autoimmune disease that is difficult to diagnose, hard to live with, and a challenge to treat. May is Lupus Awareness Month. To help raise awareness about lupus, let’s learn more about this devastating disease and explore some of the advances scientists are making in lupus research.

What is lupus?

Lupus is a group of chronic (long-lasting) autoimmune diseases that cause inflammation and pain throughout the body. There are four main types of lupus: neonatal and pediatric lupus, discoid lupus erythematosus, drug-induced lupus, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE, also referred to as lupus). The most common type of lupus, accounting for 70 percent of all cases of lupus, is SLE, which will be the focus of most of this article.

Lupus is a group of chronic (long-lasting) autoimmune diseases that cause inflammation and pain throughout the body. There are four main types of lupus: neonatal and pediatric lupus, discoid lupus erythematosus, drug-induced lupus, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE, also referred to as lupus). The most common type of lupus, accounting for 70 percent of all cases of lupus, is SLE, which will be the focus of most of this article.

The immune system usually protects your body’s organs and tissues from damage and foreign invaders like viruses and bacteria. In autoimmune diseases like lupus, the immune system messes up and begins mistakenly attacking healthy cells in the body.

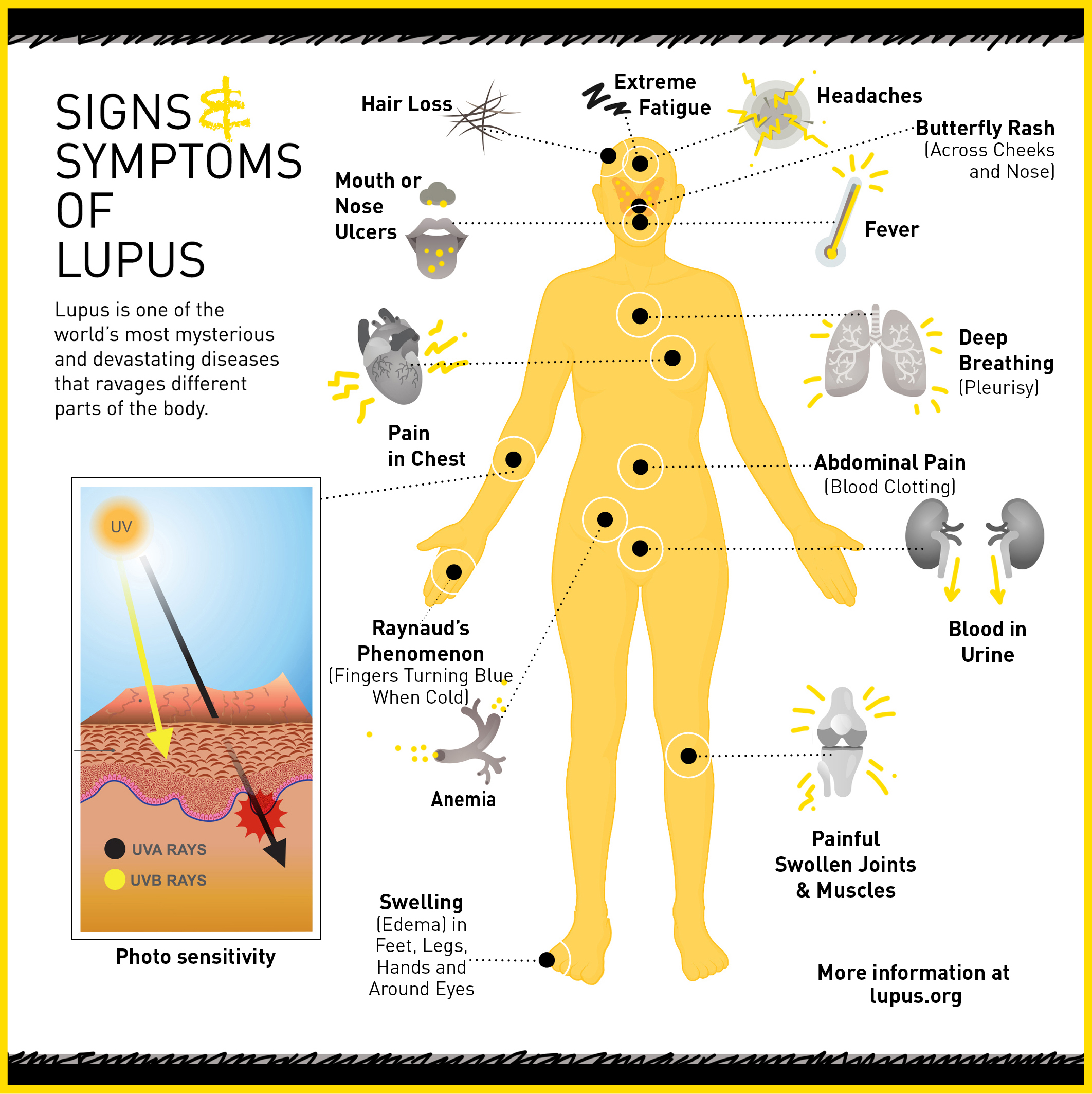

Because the dysregulated immune system can affect any organ system in the body, patients with lupus tend to suffer from widespread, chronic inflammation and tissue damage. It commonly affects the joints, skin, brain, lungs, kidneys, and blood vessels.

Symptoms and diagnosis

Symptoms of lupus are wide-ranging and differ from patient to patient depending on what organ system is affected. One telltale sign of lupus is a butterfly-shaped rash across the cheeks. Some of the more common symptoms include fatigue, joint pain and swelling, skin rashes, fever, and headaches.

It is common for symptoms in lupus to come and go in periods of symptom flare ups and periods with no symptoms, called remission. Flare-ups are usually caused by triggers such as UV radiation, certain medications, infections, colds or viral illnesses, or, like Carolyn, emotional or physical stress.

Diagnosing lupus is usually hard because it mimics the symptoms of so many other diseases. Doctors determine if a person has lupus by reviewing their symptoms and running blood tests for antinuclear antibodies or other antibodies implicated in lupus.

Unfortunately, there is no cure for lupus. Doctors prescribe different treatments to help control symptoms and minimize tissue damage. Anti-inflammatory medications help to relieve many of the symptoms of lupus by reducing inflammation and pain. Antimalarials are often prescribed for skin rashes, mouth ulcers, and joint pain, while immunosuppressive medications are used to control inflammation and the overactive immune system.

Who is affected by lupus?

There are an estimated 1.5 million Americans living with some form of lupus, and five million people worldwide. Anyone can develop lupus but certain groups are at higher risk. Nine out of ten people living with lupus are women. Most people develop the disease between the ages of 15 and 44.

Lupus is also two to three times more prevalent among women of color (African Americans, Hispanics/Latinos, Asians, Native Americans, and Pacific Islanders) than among Caucasian women. These women also tend to develop lupus at a younger age, experience more serious complications, and have higher mortality rates.

Lupus pathology

Although the first known case of lupus is thought to have been documented by Hippocrates in 400 BC, the cause of the disease remains unknown. Scientists have suggested it is likely a genetic disease triggered by environmental factors leading to defects in the immune system.

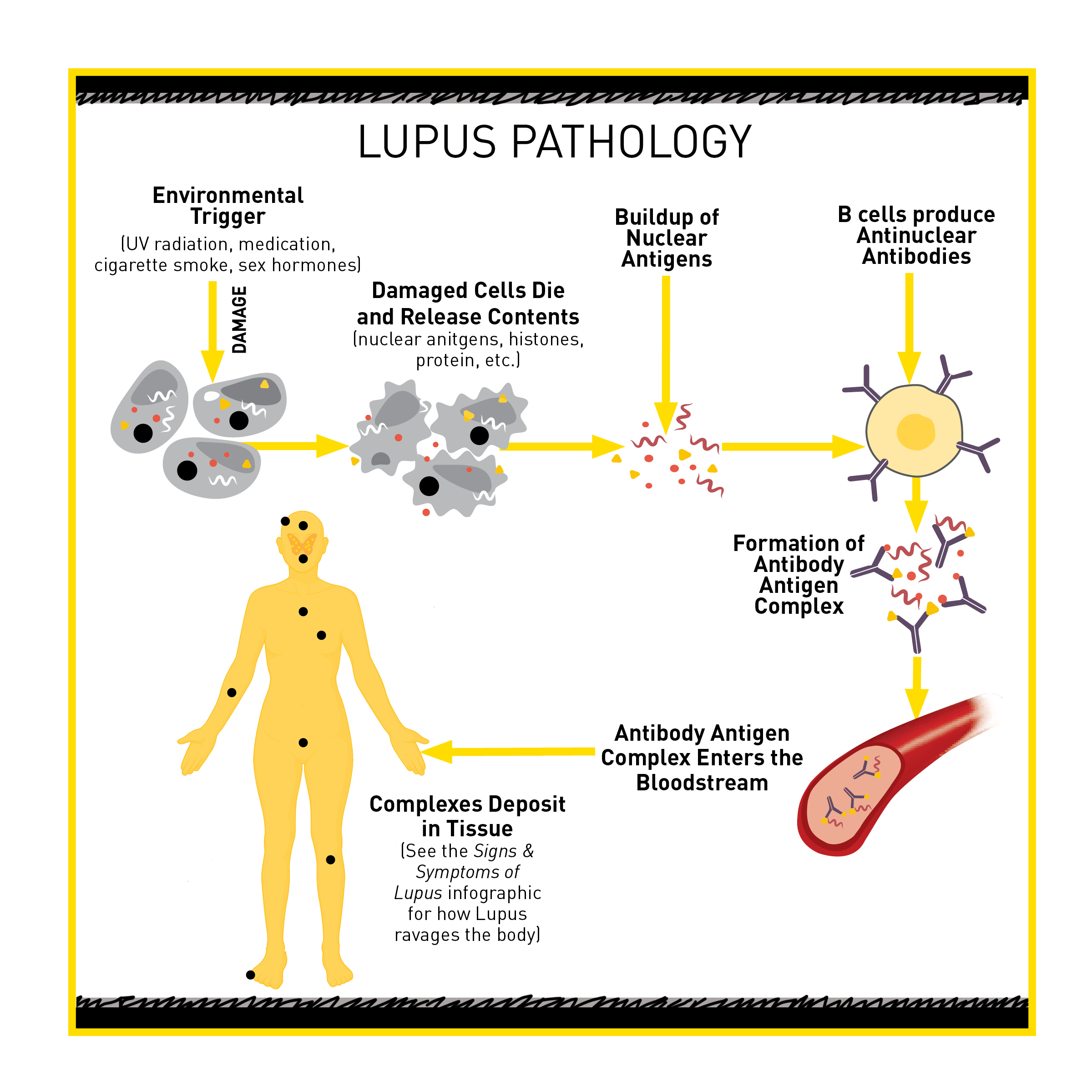

Some people, like Carolyn, seem to have susceptibility genes for lupus. When their cells are damaged by an environmental trigger such as UV light, cigarette smoke, or certain medications, they undergo programmed cell death, or apoptosis. Once the cells die, they break into many pieces, which release the cells’ content, including pieces of DNA called nuclear antigens.

Because of the person’s susceptibility genes, their immune system is more likely to think that these nuclear antigens are foreign. The immune cells will initiate an attack against these nuclear antigens. However, some people also have susceptibility genes that dampen the immune system’s ability to quickly clear the nuclear antigens so they build up. In fact, high levels of nuclear antigens are found in most lupus patients and, like we discussed above, are used as a diagnostic measure for lupus.

As part of the immune system’s attack on the nuclear antigens, B cells produce antinuclear antibodies that can recognize and bind the nuclear antigens, creating antibody-antigen complexes. These complexes float through the bloodstream and deposit in various tissues. Once in the tissues, the antibody-antigen complexes cause a localized inflammatory response which seems to be the cause of many of the symptoms of lupus.

Advances in lupus research

Advances in lupus research

Advances in medical and genomic technology have benefited the field of lupus research and improved diagnosis and disease management. These improvements allow most people with lupus to control their symptoms and live a normal life span. However, much research must be done to find a cure.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in lupus have uncovered hundreds of genetic variants linked to lupus pathology and progression. Some genetic variants explain a person’s susceptibility to developing the disease and how severe their symptoms will be.

However, genetic variants are not the only genomic change involved in the development of lupus. Chemical modifications to DNA that affect gene activity without altering the DNA sequence, called epigenetic changes, have recently been implicated in the development of lupus. At the HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology, Faculty Investigator Devin Absher, PhD, is making great strides into discovering the epigenetic influences in the development of autoimmunity in lupus.

Although lupus affects women nearly ten times more frequently than men, the molecular basis for the sex disparity is widely unknown. In a recent study, Absher and his team present strong evidence that a phenomenon called X chromosome inactivation could be involved in the disparity. Because females carry two X chromosomes compared to men who carry one, mammals evolved X chromosome inactivation to randomly silence genes on one of the X chromosomes in females. This allows for equal expression of X-linked genes across sexes.

Because X chromosome inactivation is limited to female cells, these findings may explain the female predisposition to autoimmune diseases like lupus. Silencing of certain X-linked genes in lupus patients could increase the generation of immune cells that attack the patient’s own tissue, or reduce a patient’s ability to eliminate such cells.

Epidemiological studies suggest that African American women are diagnosed with lupus at a greater frequency and severity than women of European and Asian ethnicities. However, there is a lack of representation of African American women in many of the epigenetic studies of lupus. Absher and his lab sought to remedy this deficiency in diverse data sets by studying African American women with lupus.

Results from their initial study pinpointed epigenetic differences in the way lupus affects African American women compared to other lupus patients. The team found that epigenetic irregularities in female African American patients with lupus occurred early in B cell development. This suggests that these cells may be primed for an aberrant immune response. These epigenetic differences may explain the differences in disease presentation and severity between the ethnic groups as well.

By expanding on these studies, scientists continue to look for answers to defeat this invisible monster and bring relief and a cure to patients like Carolyn.