An Everyday DNA blog article

Written by: Sarah Sharman, PhD, Science writer

Illustrated by: Cathleen Shaw

Although the disease was reported in medical accounts as early as the 1840s, it was a 22-year-old recent graduate from the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City who penned an account in 1872 called “On Chorea” that helped define Huntington’s chorea (now more commonly referred to as Huntington’s disease). The young physician, who is the namesake of the disease, was Dr. George Huntington.

When Huntington’s disease research began to ramp up in the early 1900s, scientists and physicians still cited Huntington’s account as one of the most accurate reports of the disease. Today, Huntington’s disease is still the focus of intense medical and scientific interest. Let’s learn more about this devastating disease and what scientists are doing to fight it.

What is Huntington’s disease?

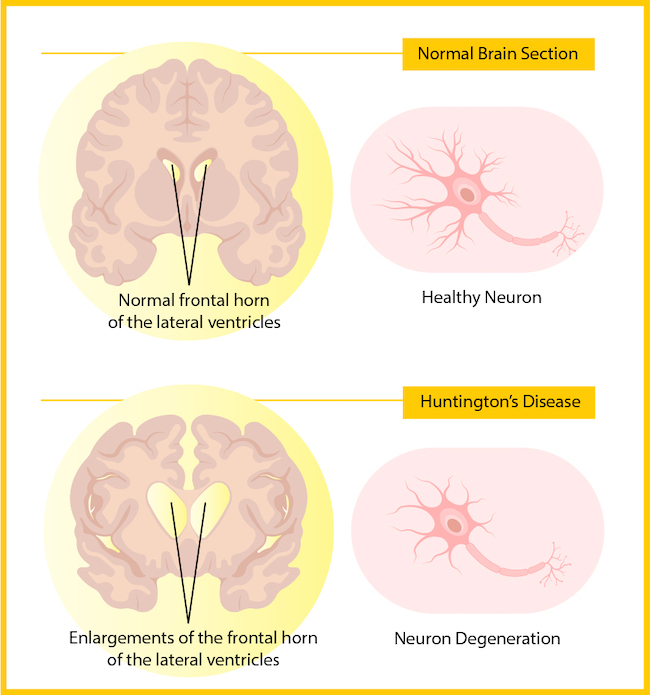

Originally described by Dr. Huntington as a ‘medical curiosity,’ Huntington’s disease is a hereditary disease that causes the progressive breakdown of nerve cells in the brain, affecting neurological and motor function. The most vulnerable part of the brain in Huntington’s disease is the striatum, which controls movement, mood, and memory.

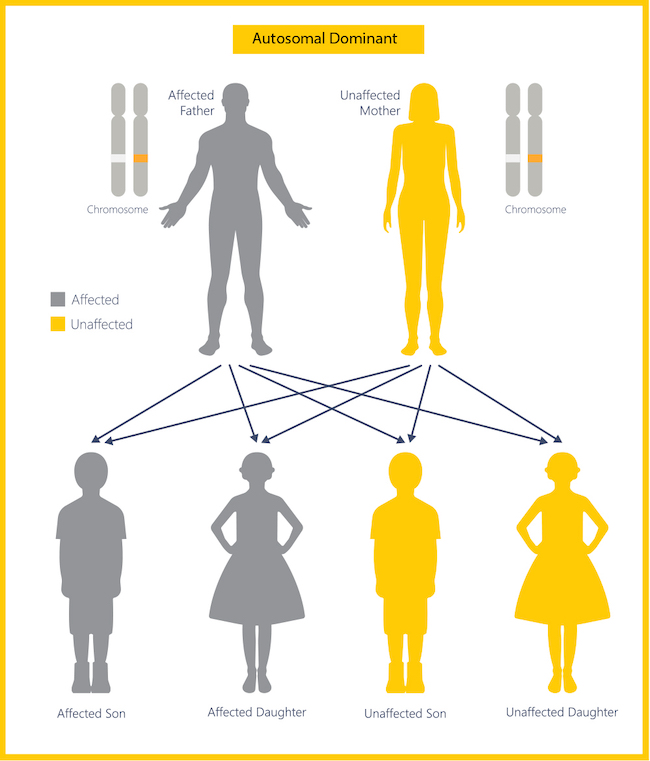

According to the Huntington’s Disease Society of America, there are about 41,000 symptomatic Americans and more than 200,000 at-risk of inheriting the disease. Huntington’s disease is an autosomal dominant disease, meaning if your parent has the disease, you have a 50 percent chance of inheriting the disease gene from them. Everyone who inherits the disease gene develops the disease.

Its original name, Huntington’s chorea, came from the characteristic involuntary, jerking movements from which people with the disease suffer. Other symptoms of the disease include abnormal body postures, changes in behavior, emotion, judgment, and cognition, and eventually impaired coordination, slurred speech, and difficulty feeding and swallowing.

Symptoms of the disease generally appear in adulthood, most often between 30 and 40 years of age, and progressively worsen over the course of 10 to 25 years. Currently, there are no treatments that have any effect on the progression of symptoms. As such, the disease is fatal, with most people dying 10 to 30 years after the onset of symptoms.

What causes the disease?

Even though Dr. Huntington described the disease in great detail in 1872, it was not until 1993 that scientists discovered the genetic cause of Huntington’s disease. An international collaborative effort known as the Huntington’s Disease Collaborative Research Group identified an abnormality in a gene known today as huntingtin (HTT) gene.

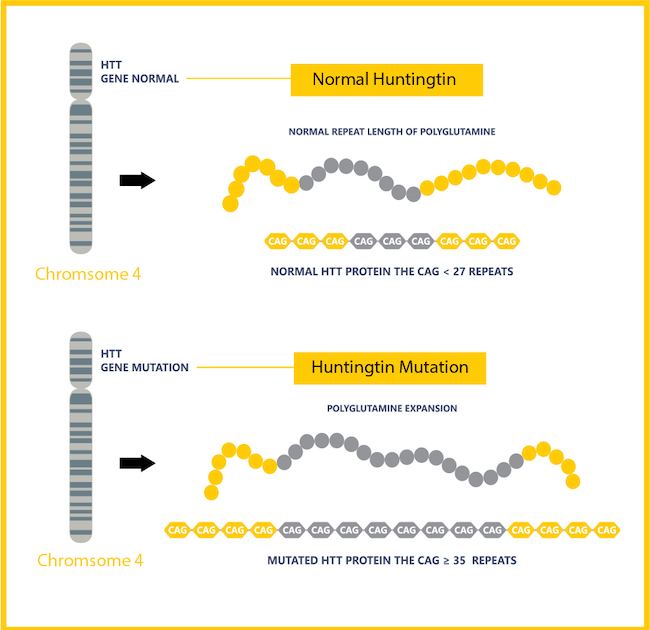

Everyone has two copies of the huntingtin gene, only those who inherit a mutated copy will develop the disease and potentially pass it on to their children. The huntingtin gene contains instructions that are copied into a biological message called RNA which makes the huntingtin protein. Huntingtin protein is very large and seems to have many functions, especially in the brain during early development before birth.

Everyone has two copies of the huntingtin gene, only those who inherit a mutated copy will develop the disease and potentially pass it on to their children. The huntingtin gene contains instructions that are copied into a biological message called RNA which makes the huntingtin protein. Huntingtin protein is very large and seems to have many functions, especially in the brain during early development before birth.

Mutant HTT is caused by additional repeated sections of nucleotides that create a larger-than-normal gene. Most people have about 20 instances of the nucleotide sequence “CAG” in the huntingtin gene. Those with a diseased HTT have around 40 or more instances of “CAG.”

The extra “CAG” nucleotides in the gene lead to an instability that causes the resulting huntingtin protein to be extra-long and difficult for the body to maintain and remove from brain cells. Over many years, the mutant protein forms clumps in brain cells, which causes them to become damaged and die (similar to those seen in Alzheimer disease pathology).

Advances in Huntington’s disease research

After the discovery of the huntingtin mutation, many hoped that a cure for Huntington’s disease would be right around the corner. Unfortunately, the disease is more complex and the quest for a cure is still ongoing. Although there is not a cure yet, much progress has been made in the Huntington’s disease field.

After the discovery of the huntingtin mutation, many hoped that a cure for Huntington’s disease would be right around the corner. Unfortunately, the disease is more complex and the quest for a cure is still ongoing. Although there is not a cure yet, much progress has been made in the Huntington’s disease field.

Numerous model systems, from cells to mice to primates, have been developed throughout the year to help scientists study the disease and explore potential therapeutics. In 2000, using one such mouse model, scientists showed that stopping production of the mutant protein after the onset of disability resulted in a reversal of symptoms and nerve cell damage in mice.

What followed were many therapeutic successes in mouse models using repurposed drugs originally developed for other diseases. However, none have been successful in reversing, delaying, or slowing the progression of Huntington’s disease in humans.

The big push in the field now is to design new therapeutics specifically for Huntington’s disease that shut down, or silence, the mutant huntingtin gene. Research on gene silencing approaches in Huntington’s disease began in 2005 and continues today.

This year, Roche and Wave Life Sciences, two pharmaceutical companies, halted their clinical trials of gene-targeting therapies for Huntington’s disease following the drugs’ disappointing performances. Both treatments use technology called antisense oligonucleotides (ASOS) that modify the production of huntingtin protein by binding to RNA sequences made by the faulty HTT gene.

At the HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology, President, Science Director and M.A. Loya Chair in Genomics, Richard M. Myers, PhD, and his lab are focused on discovering a therapeutic for Huntington’s disease. The team, led by senior scientist Brian Roberts, is studying the processes that control the expression of the huntingtin gene.

Early results suggest that the huntingtin gene may be part of a region of intense transcriptional activity, sometimes called a “transcription factory.” They hope that gaining a more thorough understanding of this region could eventually lead to novel therapeutic interventions for those suffering from the disease.

To learn more about HudsonAlpha’s Huntington’s disease research, watch this video.