The United States Department of Agriculture announced standards for labeling bioengineered foods that will go into effect at the start of 2020, though companies may choose to adopt the labeling requirements earlier. For these labels, the term ‘bioengineered’ refers to food that people commonly call GMO’s. The labeling rules aim to inject a little more information into the shopping experience, letting you know when a food has either been bioengineered or includes a bioengineered ingredient. The effort only works, though, if you understand what the labels mean.

GMO’s are a hot topic, so they can get wrapped up in passion and misunderstandings. These labels can be a great starting point to make sure we’re all operating with the same information about how the genetics of bioengineered foods work.

What does bioengineering mean? Are bioengineered foods the same as GMO’s?

What does bioengineering mean? Are bioengineered foods the same as GMO’s?

Scientist often prefer the term ‘bioengineered’ to ‘GMO’, because it’s a little more specific. GMO stands for genetically modified organism, which can lead to more confusion than clarity. After all, what counts as genetically modifying? Is it anything that changes the genes of a crop?

If that’s the case, humans have genetically modified their crops for thousands of years by breeding for productivity, hardiness or fruit and grain shape/size/flavor. Just about everything that modern agriculture produces could fall under the genetically modified label, if we understood it broadly enough.

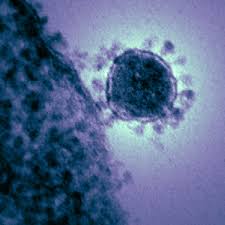

Typically, when people discuss GMO’s they’re referring to a specific type of genetic modification, where genes are added or silenced to change some important property of the crop. These modifications could increase yield, improve pest resistance or even create apples that don’t brown as easily. By singling out that process—bioengineering—the crops most commonly at the center of the GMO debates can be discussed without getting mixed up with the many other practices used to influence genetics in the agriculture sector.

How are genetics used to develop crops?

There are four primary ways that scientists attempt to improve crops, ranging from ancient to cutting edge. Understanding the different ways that scientists and farmers work to improve the fruits and vegetables that make it to your supermarket is really important if you want to understand how bioengineered foods stand out on the shelves.

Selective breeding: You might not even think of this as a genetic process, but it most certainly is. Farmers pick the plants that have the most desirable traits, then they plant seeds from those specific plants. It can lead to bigger, more resilient crops. For thousands of years, farmers have done this by examining their crops to find out which ones generate the most fruit or resist common diseases.

Selective breeding: You might not even think of this as a genetic process, but it most certainly is. Farmers pick the plants that have the most desirable traits, then they plant seeds from those specific plants. It can lead to bigger, more resilient crops. For thousands of years, farmers have done this by examining their crops to find out which ones generate the most fruit or resist common diseases.- Hybridization/cross-breeding: Here’s another genetic tool that farmers have been using for over 200 years. Farmers or scientists isolate individual plants, then cross them with others to produce new crops. This process has generated some much loved results, like seedless grapes and watermelons. It’s also how we wind up with crosses like tangelos.

- Mutagenesis: This process isn’t quite as old, only dating back to the 1920’s, but it has generated a lot of easily recognizable fruits and vegetables. Scientists use radiation or other physical and chemical disruptions that lead to mutation. They then examine the created mutations, looking for any new, desirable varieties. Those same traits can then be bred for over many generations. For example, this is how we got the vibrant color and bright flavor of Ruby Red grapefruits.

As an aside, today’s genetic sequencing helps all three of the above processes move faster. Instead of waiting for plants to reach maturity to bear fruit or test resistances, scientists can sequence plants early on to find out which ones have the genes they’re looking to promote. These breeding process are helped along by genetic sequencing, meaning researchers and farmers can develop crops more rapidly.

- Transgenesis: This is what most people think of when they think of GMO’s. To create transgenic crops, scientists make very specific genetic changes. Researchers may try to incorporate a gene that increases pest resistance or silence a gene that leads to browning. Remember the apples we mentioned that don’t brown? That’s because of a gene edit or transgenesis. We discussed it back in an earlier Shareable Science, if you’d like to know more.

All of these processes could technically be described as genetic modification, since they all lead to some change on the genetic level. However, only one of them relies on bioengineering. That’s why the term ‘bioengineered’ stands in the place where many might expect to see a label that says ‘GMO’.

What can these bioengineering labels tell us?

In 2016, Congress tasked the USDA with developing labeling standards for bioengineered food. To start with, this required definitions to operate from, in order to decide what should be labeled. The USDA determined that only foods that either resulted from transgenesis or included an ingredient resulting from transgenesis would require special labeling, found next to the nutritional information panel or on the front of the package.

That labeling comes in four potential forms:

That labeling comes in four potential forms:

- Symbols: There are accepted symbols that say either ‘Bioengineered’ or ‘Derived from Bioengineering’.

- Text Label: Producers can put text on product packaging that says ‘Bioengineered’ or ‘Contains a Bioengineered Food Ingredient’.

- Digital: Producers can make their package scannable, either through QR codes or by developing new technology. In this case, they can simply say ‘Scan for more food information’ on the label. If they use a scannable label, they are also required to include a phone number, which must be able to provide that same information to consumers 24/7.

- Text Message: Due to concerns about limited internet access for some consumers, producers also have the option to list a phone number for shoppers to text for more food information. That number would immediately respond in a text message with the same information you would get by scanning the product with a digital label.

A few important caveats are that producers are not allowed to include marketing in those disclosures, and they are not allowed to collect consumer information through them either. If you text the number for food information, the companies are prevented by law from saving your number.

Of course, the last looming question is…what gets labeled?

The USDA keeps a list of foods that come in bioengineered varieties. As of Summer 2019, that list includes certain types of:

Alfalfa

Alfalfa- Apple (ArcticTM varieties)

- Canola

- Corn

- Cotton

- Eggplant (BARI Bt Begun varieties)

- Papaya (ringspot virus-resistant varieties)

- Pineapple (pink flesh varieties)

- Potato

- Salmon (AquAdvantage®)

- Soybean

- Squash (summer)

- Sugarbeet

The USDA will keep the list updated, and if you want to read more about any of the individual crops, you can find that information here.

There are a handful of exceptions to the labeling requirements. For example, non-food products made from bioengineered foods won’t be labeled. Neither will products from animals given bioengineered feed, as the bioengineered DNA is broken down by the animal’s digestive system. Because their genetic material is removed during preparation, highly-processed foods like corn syrup or soybean oil aren’t required to carry the label, even if derived from bioengineered plants. The labeling rules also won’t apply to foods developed through the newer “gene-editing” techniques like CRISPR, because they don’t contain DNA from other organisms and mimic the spontaneous genetic variation that occurs through natural selective breeding. Some manufacturers have announced their intention to voluntarily disclose the presence of these exceptions alongside those required by law.

Everything in its right place

We need meaningful conversations about the way we can use genetics to improve our crops. However, those conversations can only be meaningful if we understand each other. Hopefully, you have a firmer grasp of the variety of ways scientists and farmers develop crops and what qualifies as bioengineering. These labels do not imply that bioengineered foods have a different health or safety profile. They provide more clarity and information for shoppers making their way through the grocery store. Understanding the genetics behind the issue, provides you with additional insight into the meaning and the science behind the labeling.

Of course, as with all science, it’s best when shared!

To schedule a media interview with Dr. Neil Lamb or to invite him to speak at an event or conference, please contact Margetta Thomas by email at mthomas@hudsonalpha.org or by phone: Office (256) 327-0425 | Cell (256) 937-8210

Get the Latest Sharable Science Delivered Straight to Your Inbox!

[gravityform id=19 title=false description=false ajax=true][wprpw_display_layout id=8]